Cancer Prevention Month: The Risks Associated with Alcohol Consumption

February is national cancer prevention month, an awareness campaign by the American Association for Cancer Research to support research on prevention. Cancer is the largest cause of death in Canada. It is expected that 254,000 Canadians have been diagnosed with cancer in 2025 and 87,400 have died due to cancer-related illnesses (1). According to the Canadian Cancer Society, about 40% of cancers can be prevented through healthy living and policies designed to protect the health of Canadians. The Canadian Cancer Society recommends the following: live smoke-free, be sun safe, have a healthy body weight, eat well, move more/sit less, and limit alcohol.

In this blog, I will review the research and guidance surrounding alcohol consumption and how it relates to our health, with a particular focus on cancer. Whenever I talk about how many “drinks” a person has throughout this blog, I will be talking about a standard drink. In Canada, a standard drink is about 17mL of pure alcohol. This corresponds to a standard bottle (341mL) of 5% beer, cider, or cooler, 142mL (5oz) of 12% wine, and 43mL (1.5oz) of 40% spirits. Definitions are provided for other words in bold at the end of this blog.

Alcohol and Cancer

According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer, part of the World Health Organization, alcohol has been classified as a group 1 carcinogen. This means that there is sufficient evidence that it causes cancer in humans. There is substantial evidence that alcohol is a major risk factor for cancers of the mouth, throat, esophagus, liver, colon, rectum, and breast. There is also emerging evidence that alcohol increases the risk of stomach and pancreatic cancer (2). People often underestimate the risk that consuming alcohol has on cancer. In a survey conducted by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA), only 26 to 34% of people were aware that alcohol was a risk factor for certain cancers, with 35 to 44% believing it had no impact on cancer risk at all (3). Increasing awareness is the first step towards shifting behaviour and reducing cancer risk.

What does the research say?

There are numerous studies on the negative health effects of alcohol, but I would like to focus on one particular study: Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 (4). This is by far the most comprehensive review of the global alcohol burden, which was published in The Lancet in 2018.

Although researchers have long recognized alcohol as a risk factor for mortality, some evidence suggested that low intake may have a protective effect on certain conditions such as ischemic heart disease and diabetes. Recently, the methodology of these studies has been questioned, and the Global Burden of Disease Collaborators sought to comprehensively re-evaluate the data. In this study, the authors recalculated and improved previous estimates of alcohol use and used updated analytic techniques to calculate the association between alcohol and 23 health outcomes, including cancers, cardiovascular diseases, unintentional injuries, and self-harm.

The results were staggering. In 2016, 2.8 million deaths were attributable to alcohol globally. Alcohol was ranked as the 7th leading risk factor for premature death and disability and 1st among those aged 15 to 49. In high sociodemographic index countries, like Canada, cancers accounted for 27% of alcohol-related deaths among men and 19% among women. This doesn’t mean alcohol causes 27% of cancers, just that among deaths linked to alcohol, cancer was the biggest contributor. Of the 23 outcomes that were analyzed, 20 showed that relative risk significantly and consistently increased with increasing alcohol consumption. The minimum consumption level to reduce risk of these outcomes and all-cause mortality was 0 drinks daily. Altogether, this means that any amount of alcohol consumed (1) caused an increase in risk in the outcomes evaluated and (2) caused an increase in mortality from any cause.

This paper was important because it changed much of the world’s perception on alcohol consumption and its burden on the global population. The authors stressed that there was a need to revisit alcohol control policies and health programs, and to consider recommending abstention.

What about the positive effects of alcohol?

Previous research has emphasized positive effects of alcohol, such as reducing the risk of heart disease, stroke, and diabetes when consumed in low amounts. In fact, this research influenced previous guidance on alcohol consumption and was part of the reason the Global Burden of Disease Collaborators re-analyzed the findings. The current consensus is that there is no significant association between low alcohol intake and these health benefits, and at high intakes it leads to increased risk. There is also the misconception that alcohol can potentially aid in relaxation and social bonding, which may offset its negative effects at lower levels. In fact, it is exactly the opposite. While drinking small amounts can have social benefits, and stronger social relationships can lower all-cause mortality, this is significantly outweighed by the numerous negative effects. The reality is that mortality consistently increases with increasing alcohol consumption, and the only level of alcohol consumption that completely avoids increasing risk of mortality is zero.

Canada's Guidance on Alcohol and Health

Many people believe that the guidelines for alcohol consumption are 1 drink per day for women and 2 drinks per day in men. There are two problems with this advice: 1) alcohol consumption guidance has recently been updated; and 2) this was not what the original guidelines previously stated. In 2011, the CCSA released the following guidance on alcohol consumption:

- To reduce long-term health risks, drink no more than 10 drinks per week for women and 15 drinks per week for men, with no more than 2 drinks per day on most days.

- To reduce short-term health risks, have no more than 3 drinks per day for women and no more than 4 drinks per day for men.

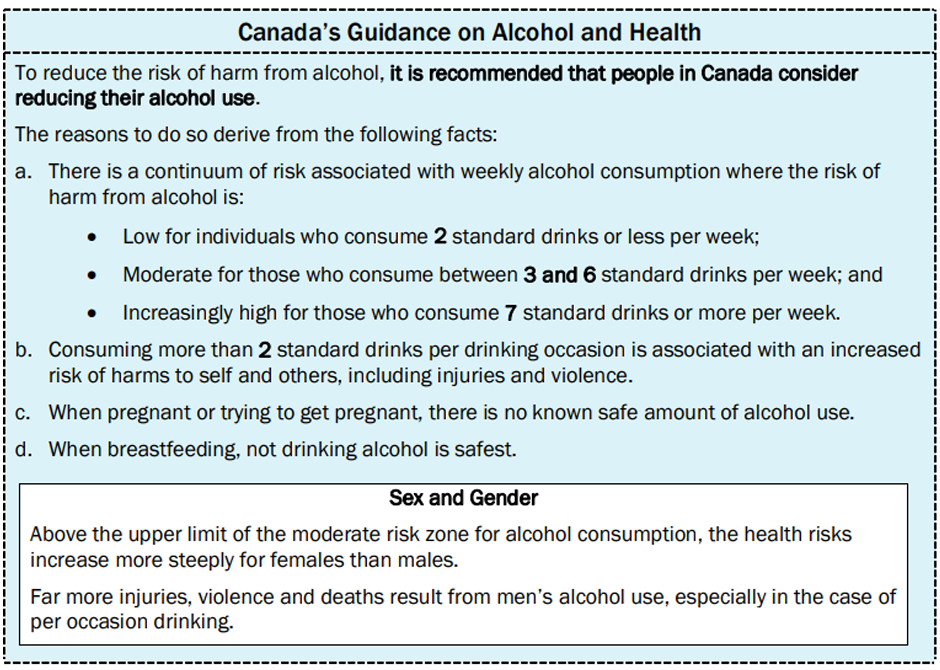

As I mentioned, this guidance was updated in 2023 (5). These are the updated guidelines:

Why were the guidelines updated?

There is no set timeline that determines when the government updates its guidance for any particular item. In this case, there were a few reasons which pushed them to update the guidance on alcohol consumption:

Evolving and increasing knowledge: Since 2011, many studies have been published outlining the association between alcohol and several diseases, including the one described above. Eventually, there was enough new information to prompt an update.

Adherence to current guidelines was still associated with increased risk: A Canadian study done in British Columbia in 2020 showed that many people adhering to the 2011 guidelines were still experiencing adverse health effects, including alcohol-associated cancer deaths, hospital stays due to unintentional injuries, and deaths due to digestive conditions and other injuries (6).

Other countries were updating their guidance: Countries like the United Kingdom, France, Denmark, Holland, and Australia were all releasing new guidance with lower weekly limits.

If alcohol causes so many adverse health effects, why doesn’t the CCSA recommend not drinking?

It’s a common misconception that the guidance from the CCSA tells Canadians what the safe amount of alcohol consumption is or “how much people can drink.” As previously discussed, there is no truly safe amount. However, while it is true that any amount of alcohol consumption increases the risk of mortality, that is not exactly useful information for most Canadians. The purpose of the CCSA guidance is to help people make well-informed and responsible decisions about their consumption of alcohol.

Throughout life, we are exposed to many risks, and there are varying levels of risk people are willing to accept. For risks associated with voluntary activities (such as drinking, skydiving, and other activities), people are generally willing to accept a 1 in 1000 risk of premature mortality as being “low risk” and a 1 in 100 risk of premature mortality as “moderate risk.” This is the foundation for Canada’s guidance on alcohol and health. Consuming 2 drinks per week is low risk, meaning there is at most a 1 in 1000 chance of premature death from alcohol. Consuming 3 to 6 drinks per week is moderate risk, meaning there is at most a 1 in 100 chance of premature death. Finally, the risk of premature mortality from consuming 7 or more drinks per week is “increasingly high.” This means that for each additional drink you have, your risk of mortality will increase.

Practical Tips for Reducing Alcohol Use

The best practical advice for reducing alcohol consumption is to plan to drink less. Set a weekly drinking target and do your best to stick to it. Here are a few tips to help you meet your goals:

- Drink slowly: Planning to have a certain number of drinks will help with this.

- Alternate alcoholic drinks with non-alcoholic drinks

- Drink plenty of water: alternating alcoholic drinks with glasses of water is a great way to reduce consumption while staying hydrated.

- Eat before and during drinking: Try and make a plan to eat if you know you will be out for an extended period.

- Plan alcohol-free weeks

- Choose sober activities

- If you are planning to drink, try not to exceed 2 drinks per day: This will minimize your risk of harm to yourself and others.

Remember, you can reduce your drinking in steps and every drink counts. Any reduction in alcohol use has benefits.

If you or someone you know may be struggling with alcohol use, you are not alone — and support is available. Reaching out can feel difficult, but help from a health care provider, counsellor, or peer support program can make a meaningful difference. Alcoholics Anonymous is a well-established peer support group offering free confidential meetings. SMART Recovery Canada is another evidence-based self-management and recovery group that supports people in overcoming addictive behaviours. If you’re not sure where to begin, consider speaking with your family doctor or exploring local community resources.

Definitions

All-cause mortality: Quite simply, this means dying from any cause. Researchers are generally interested in the number of deaths from any cause, such as cancer, accidents, infections, etc., in a group of people over a set time. This is important because people care about staying alive overall, not just avoiding any one specific disease.

Carcinogen: Any substance, exposure, or agent that can raise cancer risk over time. They are classified as group 1 (carcinogenic to humans), group 2A (probably carcinogenic), group 2B (possibly carcinogenic), and group 3 (not classifiable).

Relative risk: Compares how likely one event is to occur in one group versus another. For example, if someone is twice as likely to develop cancer because they drink alcohol regularly, we say their relative risk is 2. In practice, if your baseline risk of developing cancer is 10%, a relative risk of 2 would mean your risk is now 20%. It’s important that relative risk is always comparing two different groups. This is distinct from absolute risk, which is your actual risk of an event happening.

Follow the Patterson Institute for Integrative Oncology Research on socials for more:

Mark is a full-time research coordinator with the Patterson Institute for Integrative Oncology Research. He is involved in the development, implementation, day-to-day activities, and publication of all research conducted at the CHI. Mark joined Dr. Dugald Seely, ND’s research team in 2018 after volunteering with his brother, Dr. Andrew Seely, at The Ottawa Hospital. Mark is also an employee of The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, a Certified Clinical Research Professional (CCRP), and an active member of both the Canadian College of Naturopathic Medicine and Ottawa Health Sciences Network Research Ethics Boards.

References

- Canadian Cancer Statistics (2025).

- Bagnardi V, Rota M, Botteri E, et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose–response meta-analysis. British Journal of Cancer. 2015/02/01 2015;112(3):580-593. doi:10.1038/bjc.2014.579

- Public awareness of alcohol-related harms survey 2023 [Web Summary] (2023).

- Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. Sep 22 2018;392(10152):1015-1035. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31310-2

- Paradis C, Butt, P., Shield, K., Poole, N., Wells, S., Naimi, T., Sherk, A., & the Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines Scientific Expert Panels. Canada’s Guidance on Alcohol and Health: Final Report. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA). 2023.

- Sherk A, Thomas G, Churchill S, Stockwell T. Does Drinking Within Low-Risk Guidelines Prevent Harm? Implications for High-Income Countries Using the International Model of Alcohol Harms and Policies. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. May 2020;81(3):352-361.

CHI Services

All Services

Supportive Cancer Care

Naturopathic Medicine

Acupuncture & TCM

Integrative & Functional Medicine

Nurse Practitioner Care

IV Therapy

Psychotherapy & Counseling

Grief Support

Hypnosis & Life Coaching

Yoga Therapy

Physiotherapy & Lymphatic Therapy

Osteopathy

Reflexology

CranioSacral Therapy

Massage Therapy

Nutritional Support & Meal Plans

Fees & Schedules

Please see our online booking site regarding fees and schedules.